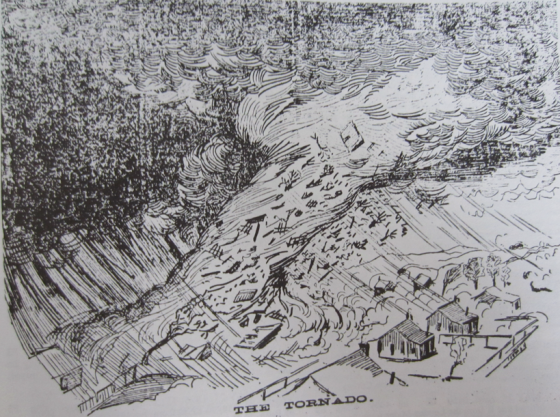

Damage photographs are the most important tool in ascertaining the strength of historical tornadoes. Shown above is probable EF5 damage near Colfax, Wisconsin, after a powerful tornado ripped through the area in 1958. Trees of all sizes were debarked, ground vegetation was scoured and vehicles were rendered unrecognizable. (Image courtesy of the University of Wisconsin Digital Collections)

□ Categorizing powerful tornadoes is a very, very inexact science. Most tornadoes capable of causing EF5 damage fail to impact populated areas, and the chance of any single storm impacting a man-made structure while at peak intensity is exceedingly small. Statistics on path length, width and forward speed are rarely accurate for historical events, further complicating analysis.

While nowhere near definitive, objectivity is attempted through the use of damage photographs, reliable survey reports and fatality statistics. Unverified accounts, vague newspaper descriptions and damage figures are not considered. Tornadoes that occurred before 1880 and tornadoes that caused less than 10 deaths are excluded to eliminate the thousands of rural storms that failed to attract significant media attention. Little to no photographic evidence makes the inclusion of some past tornadoes infeasible without further information.

The indefinitive list of the strongest tornadoes from 1880 to 1969:

1. Sherman, Texas – May 15, 1896

2. De Soto/Murphysboro/West Frankfurt, Illinois – March 18, 1925

3. New Richmond, Wisconsin – June 12, 1899

4. Beecher, Michigan – June 8th, 1953

5. Hudsonville, Michigan – April 3, 1956

6. Tupelo, Mississippi – April 5, 1936

7. Udall, Kansas – May 25, 1955

8. Pomeroy, Iowa – July 6, 1893

9. Woodward, Oklahoma – April 9, 1947

10. Scott County, Mississippi – March 3, 1966

11. Ruskin Heights, Missouri – May 20, 1957

12. Snyder, Oklahoma – May 10, 1905

13. Colfax, Wisconsin – June 4, 1958

14. Gans, Oklahoma – January 22, 1957

15. Winston County, Alabama – April 20, 1920

Since the turn of the 20th century in the US, only the Tri-State event has claimed more lives than the Tupelo tornado (shown above). Despite the storm’s exceptional intensity and high death toll, it was largely forgotten amidst the turmoil of the Great Depression. At left, the tornado scoured patches of vegetation from the ground and hurled debris and dozens of bodies into Gum Pond. Large plantation homes were swept completely away on the west side of town. The final number of fatalities from the storm may have exceeded 240, making it the worst single tornado disaster in a US town.

____________________________

4. Beecher, Michigan – June 8th, 1953

The Beecher tornado left a narrow swath of extreme damage along Coldwater Road. At left, a vehicle that was thrown into the basement of an obliterated home. At right, the swath of F5 damage around the local high school. Grass scouring was documented throughout the tornado’s path. The fatality rate within the F5 damage contour was exceptionally high, including more than 60 deaths in a quarter mile stretch centered on Saginaw Street. (Flint Public Library)

□ Prior to the 2011 tornado season, the year 1953 was the deadliest in contemporary American history. Prolific severe weather outbreaks brought catastrophic tornadoes from central Texas to Massachusetts, with much of the activity focused within a three-week period beginning in the middle of May. The deadliest and strongest tornado of the year began its path of destruction northwest of Flint, Michigan, just before dark on June 8th. Spawned from a violent supercell thunderstorm with baseball-sized hail, the devastating tornado spent its first few minutes ripping through farmland north of Daltons Airport. The tornado quickly developed a violent inner core that left a path of pronounced ground scouring as it roared eastward at more than 40mph. Five miles after first touching down, the F5 tornado reached the Flint suburb of Beecher.

Huge strokes of lightning momentarily lit up the “column of storm clouds” as it crossed Ballard Drive and entered a two mile stretch of residential developments east of the yet-to-be-constructed I-475. Entire families were killed as homes were swept completely away within a 150-yard wide path that travelled roughly parallel to Coldwater Road. Most survivors in the streak of worst damage later described regaining consciousness more than 50 yards from their devastated homes, sometimes near the bodies of relatives or neighbors (Flint Public Library). Trees were snapped just above ground level near a local high school, and vehicles were hurled several blocks and rendered completely unrecognizable. After passing through Beecher, the tornado travelled an additional 15 miles before finally dissipating in rural Lapeer County. When the final victims succumbed to their injuries a few months later, the death toll stood at 116, with five families suffering four or more fatalities. The tornado was the deadliest of the weather radar age (post-1950) in the US until it was surpassed by the 2011 Joplin tornado

The Beecher tornado occurred during the climax of a severe weather pattern that favored the development of violent tornadoes in and around the Great Lakes region . Following the Palm Sunday outbreak of 1965, the locus of severe weather outside tornado alley shifted southward towards Indiana and northern Alabama. While no E/F5 tornadoes have impacted Michigan since the 1950’s*, the Beecher tornado is a reminder that exceptionally violent tornadoes are capable of developing well outside the prairies of Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas.

*A tornado that struck Strongsville, MI was likely capable of causing F5 damage. Additionally, the majority of tornadoes capable of causing F5 damage are not rated as such.

Unlike the Waco, Texas, tornado a few weeks earlier, the Beecher tornado left damage indicative of EF5 intensity. A videographer captured pronounced ground scouring in rural areas outside town. The ground markings were indicative of extremely powerful suction vortices that rotated around the core of the storm (Flint Public Library / Right video stills by Ken Kelley)

The tornado travelled almost due east down Coldwater Road for several miles. This photograph was taken near the eastern edge of the residential developments in Beecher and shows almost the entire swath of damage through the suburb. Most of the fatalities occurred within a half mile of the water tower on Saginaw Street (visible above).

At left, a picture of the swath of complete devastation along Coldwater Road. At right, closer view of empty foundations near Saginaw Blvd.

3. New Richmond, Wisconsin – June 12, 1899

The New Richmond tornado caused catastrophic wind damage to homes and businesses along the Willow River. This photograph was taken after several days of moderate clean-up, but the scene resembles the “not a board left standing” description printed in newspapers the day after the disaster. (University of Wisconsin Digital Collection)

□ On a summer afternoon in 1899, the normally quiet streets of New Richmond were populated with out-of-towners who had come to see the Gollmar Brothers Circus. As the performances came to an end around 5 o’clock, residents and tourists alike filled the streets in the center of town. Several miles outside New Richmond, a powerful tornado was thundering along the banks of the Willow River. Just after 6pm, the approaching tornado became visible from town, causing an immediate panic to surge through the crowds. Most locals ran towards their homes, while others fled into the brick and mortar businesses that lined 1st Street. Less than two minutes later, as the last few scrambled through the now-empty streets, the storm’s roar became deafening. Clouds of dirt and debris were whipped into the air as the tornado tore through 16 blocks of homes and businesses on the northern side of town. At least 114 people were killed as buildings were swept completely away within a 300-yard wide strip of devastation. Some of the victim’s bodies were blown several blocks and later recovered from the waters of Mary Park Lake. Local newspapers documented a 3,000lb safe that was hurled approximately 100 yards and a dead horse that was thrown two miles. The wide visibility of the storm likely prevented the death toll from climbing much higher.

Damage photographs show a clear swath of F5 damage that swept the ground clean along the shores of the Willow River. Photographic evidence also reveals that trees were debarked and debris from destroyed buildings was finely granulated, both indications of extreme intensity. While records from the 19th century are rarely reliable, the storm’s official fatality to injury ratio is among the highest of any tornado in history. The New Richmond tornado remains the worst in Wisconsin’s history, and the deadliest summertime tornado on record.

Approximately a dozen people were killed in the basement of a brick store that was obliterated on 1st Street. At right, view of debarked trees and flattened buildings in the center of town. The tornado hurled a 3,000lb safe an entire city block – this remains one of the most impressive instances of tornado damage ever documented (University of Wisconsin Digital Collection)

At left, the remains of the Nicollet Hotel, once a large, three-story brick building. At right, closer view of the swath of F5 damage through the northern side of New Richmond. (University of Wisconsin Digital Collection)

2. Murphysboro, Illinois – March 18, 1925 (Tri-State Tornado)

The deadly Tri-State tornado caused an exceptionally high number of fatalities in southern Illinois. More than 200 deaths occurred in less than 90 seconds as the storm erased a large section of Murphysboro, pictured above. (Image by Sue Stinson)

□ In the spring of 1925, the deadliest and most destructive tornado in United States history touched down in the tree covered hills of Reynolds County, Missouri. The storm initially struck few buildings as it slowly intensified and roared to the east-northeast at more than 65mph. Only 11 fatalities were recorded in the 85 miles before the storm crossed the state border into Illinois. Some survivors in southeastern Missouri later reported seeing “funnels” early in the tornado’s life, but the storm quickly became diffuse and unrecognizable within a column of heavy rain and hail.

The tiny town of Gorham, with only a few hundred residents, was the first populated area to experience F5 damage. One in six residents perished as the storm swept away most of the town’s homes, many of which were never rebuilt. Citizens of Murphysboro, a small city eight miles east of Gorham, later described an inpenitrable darkness that descended over the area just before the tornado struck at 2:30pm. For many, the roar of the storm was the only warning that preceded the “heavy cloud” as it tore a half-mile wide swath of complete devastation through the northern side of town. The tornado struck with such power that it wiped out entire families, including eight households that reported four or more deaths (Genealogy Trails). Damage throughout the city was inconsistent – a row of homes in the center of the tornado’s path was battered but left standing while adjacent homes were swept away, an indication the tornado had a complex multiple vortex structure. In total, 234 people were killed in Murphysboro. More than half of the deaths occurred within four blocks of the intersection of 16th and Gartside Street.

A few minutes after exiting Murphysboro, the exceptionally powerful tornado obliterated the town of De Soto, leaving only debarked stumps and pulverized bits of debris in its wake. Of the 69 deaths in and near the small town, 33 were in one brick school that was obliterated. At 2:50pm, the tornado ripped through a housing subdivision in West Frankfurt, a mining town filled with the wives and children of miners working deep underground. Only the northwest corner of town was clipped by the storm, but the destruction was complete. The dollar damage in West Frankfurt totaled only a fraction of what was recorded in Murphysboro, yet a total of 127 lives were lost, including seven deaths in one family (Genealogy Trails). The tornado maintained exceptional intensity as it thundered eastward towards the Indiana border. More than 30 farm owners were killed in rural homesteads in southeastern Illinois, an unprecedented figure indicative of the tornado’s exceptional intensity (Tom Grazulis, 1994). The mangled body of one farmer from the town of Parrish was found more than a mile from his obliterated home (Quigley, 1996).

In Indiana, the tornado continued to pave an unbroken swath of F4+ damage. The storm’s forward speed accelerated to 73mph as the surrounding rain and fog lightened, occasionally providing survivors glimpses of “multiple funnels” (Grazulis, 1993). Dozens were killed in the town of Griffin, a tiny railroad community only two blocks wide. After traveling more than 200 miles, the tornado finally lifted near Union, Indiana.

Survivor descriptions of the Tri-State tornado are reminiscent of footage captured during the 2011 Joplin tornado. Unlike the Joplin storm, however, the 1925 event was fast moving and not preceded by extensive warning. The Tri-State storm struck only small towns and rural areas during its three and a half hours on the ground yet caused approximately 700 fatalities. While some meteorologists suggest the disaster may have been a closely spaced family of tornadoes, the damage path was uniform in size, intensity and direction through all of Illinois, where most of the destruction occurred. In terms of longevity and intensity, the storm remains the single most impressive tornadic event ever documented.

Four views of probable F5 damage in Murphysboro. At top left, erratic damage patterns hint at the storm’s multiple vortex structure, though fires from broken gas lines may have contributed to the sharp damage contour. The concentration of fatalities in Murphysboro was remarkably high, with some neighborhoods losing more than half their population to the storm.

At top left, the De Soto school were 33 students were killed. At bottom left, survivor descriptions from Murphysboro indicate the tornado was preceded by heavy rain and hail which blackened the sky, much like the 2011 Joplin tornado (pictured). (Video still by Darin McCann) At right, damage in West Frankfurt, where dozens of homes were swept completely away.

The swath of empty foundations in the northwest corner of West Frankfurt, where the highest concentration of fatalities occurred.

1. Sherman, Texas – May 15, 1896

One of the most powerful tornadoes in history cut a narrow path of complete devastation through a neighborhood in Sherman, Texas. The storm was likely similar in appearance to the 2007 Elie tornado, which also rapidly intensified several minutes before lifting. While the Elie storm was powerful enough to rip a home from its foundation, it moved significantly slower and was undoubtably less intense than the Sherman event. The 1896 tornado season was one of the deadliest on record, largely due to a weaker storm (F3/marginal F4) that killed over 250 in the St. Louis metro area on May 27th.

□ Old newspaper accounts, full of embellishments and divine prophetics, are rarely useful in ascertaining the intensity of historical storms. With that said, one particular tornado transcends the information haze that preceded the turn of the 20th century. The devastating and exceptionally powerful storm touched down 40 miles north of downtown Dallas, Texas, on a muggy May afternoon in 1896. Survivor testaments collected by Tom Grazulis indicate that the violent storm never took on the “wedge” shape commonly associated with F5 tornadoes and instead appeared as “a perfect funnel” (Grazulis, 1993). After traveling northeast for more than 40 minutes and taking a dozen lives, the tornado entered its shrinking stage and made an abrupt curve to the north, sparing the center of Sherman. The drill-like funnel carved an extremely narrow path through a mixed-racial neighborhood on the western side of town. Less than 60 homes were destroyed, but most were swept completely away. Half of the 60 deaths in Sherman were concentrated within eight separate homes in which most or all occupants perished (link). Newspapers reported that most of the victims were thrown long distances, many more than 400 yards (Grazulis, 1993). One of the bodies was found in a tree four blocks from a home that was swept completely away. The ground within the streak of devastation was scoured, and an iron bridge on Houston Street was ripped from is anchor bolts and fragmented into “useless scraps.”

The Sherman tornado remains one of the most powerful tornadic events ever documented. Tom Grazulis considered the tornado the most impressive of all 19th century events based on newspaper descriptions of the damage. If a more comprehensive list of the “strongest tornadoes” were created, the Sherman tornado would likely deserve a place at the top.

One of the few available damage photographs showing the aftermath of the Sherman tornado. According to Grazulis (1993), the primary damage path through the city was only 60-yards wide. Strangely, newspapers reported that most of the bodies were found to the south of their destroyed homes, the opposite direction of the storm’s movement.

*Tornadoes that likely belong on the list include:

Clyde, Texas – June 10, 1938 – Slow moving storm caused possible Jarrell-type damage.

Antlers, Oklahoma – April 12, 1945 – Damage photographs inconclusive.

Rocksprings, Texas – April 12, 1927 – Extremely violent tornado for southwest TX.

Fargo, North Dakota – June 20, 1957 – Caused streak of extreme damage in Golden Ridge.

This site (while containing some inaccurate statistics) has some great photos that I have been unable to find anywhere else. Specifically, the link called “Shauna Williams Photos” has a couple photographs of “incredible phenomena”

I must admit that I am surprised that the Gainesville, Fort Smith, Worcester, and Topeka events did not make this list. However, I must applaud you for including the Ruskin Heights tornado. The only highly notable tornado that has occurred where I grew up, and stories of which helped fuel my interest in severe weather.

If there’s anything inaccurate (assuming you mean my site), then I’d prefer if you pointed it out so I can make the change.

For all the tornadoes described above, I actually contacted the local libraries in Flint, New Richmond, Jackson County and Lee County and exchanged e-mails, difficult-to-find web archives and sometimes photographs (hence they aren’t found anywhere else) with local historians.

As for the list, it will probably go through some edits, but I spent a few weeks researching every F5 or possible F5 that caused more than 10 deaths, including Worcester/Topeka/Gainesville (1902 and 1936) and this is what I felt seemed most accurate. The Topeka storm caused very few deaths despite passing right through downtown, an indication the storm was widely visible, fairly slow-moving and not exceptionally intense. It swept away small, likely frail tract homes, but didn’t cause much debarking/ground scouring.

What is your opinion on the 1905 Snyder? That one boggles my mind.

The Snyder tornado, along with a few other deadly Oklahoma/Texas storms, were likely incredibly intense due to the high number of fatalities. There are no good images that I can find of the Snyder damage, however, and no reports of ground scouring or other incredible phenomena, so I wasn’t able to include it.

Oh, sorry, I meant to provide a hyperlink: http://genealogytrails.com/ill/jackson/1925tornado_shauna.html I meant this site, not yours, my mistake.

I meant this site might have some inaccurate statistics, not this one.

A great forum for any of your lists…has great photos of damage from tornadoes old and new: http://www.talkweather.com/forums/index.php?/topic/58889-significant-tornado-events/page__st__0

Because I here it mentioned in every article of it, how was the forward speed of the Tri-State calculated, given how long ago it was? Is it based on the times recorded in locations, a formula on how fast it would have had to move to arrive there, or something? Because I doubt anyone tried to time it.

The forward speed was based on the times it impacted different towns as that was the only method available pre-radar.

The Tri-State tornado remains “the fastest” tornado on record when, in fact, many tornadoes, violent and weak, have surpassed 73mph. Analyzing radar from 4/27/11, I believe some of the tornadoes may have reached forward speeds of 80mph for brief periods.

The Comanche tornado happened way back in 1860 and people in Iowa are still talking about it!!

that and the Grinnell and Pomeroy

I see the NWS rated the 1957 Gans Tornado an F4. I can’t find much info on it, but why is it on the list? Also, why are the Udall and Woodward tornadoes not near the top of the list?

My personal ranking, at least with what I know right now, would be

1. Tri-state (worst of the worst in every way)

2. Woodward (swept away entire towns, travelled so far)

3. Udall (crazy vehicle damage, 80 deaths in one tiny town)

4. Hudsonville (ground scarring, not a stick left on the empty foundations)

5. New Richmond (the pictures you posted are very convincing, complete destruction)

6. Sherman (maybe higher, but not many damage photos from that time)

7. Tupelo (more than 230 deaths in a Mississippi town in the 1930’s, high death rate, mansions swept away)

8. Pomeroy (looked up some pictures after seeing it here and it looks wild)

9. Flint/Beecher (ground scarring. maybe should be higher up)

10. Colfax

Lee –

The Gans tornado was a highly unusual mid-winter/early morning storm that dug deep ditches into the ground and threw bodies and heavy items more than half a mile. It caused the most intense ground scouring of any tornado I’ve ever read about besides the 2011 Kemper County Tornado.

The Woodward tornado is not higher on the list because I have yet to find any damage photographs or reliable reports that indicate it was “exceptionally” intense. The town of Glazier was swept away, at least according to one infamous image, but it’s hard to know what exactly was there beforehand.

As for the Udall tornado, there are tons of pictures of the damage so I have a good understanding of its intensity when it passed through Udall. The damage is intense, definitely F5 worthy, but only a few homes were swept completely away. Also, trees throughout town were partially, but not completely, debarked. Looked more intense than Greeensburg, but probably a bit weaker than the Parkersburg storm.

Pingback: The Indefinitive List of the Strongest Tornadoes Ever Recorded (Part I) |

Two Flickr albums of damage from the Candlestick Park tornado, if you’ve been looking for some:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/mississippi-dept-of-archives-and-history/sets/72157631085464320/with/7790350898/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/mississippi-dept-of-archives-and-history/sets/72157630282970616/with/7686952720/

For the second link, go to the very bottom row on the first page for tornado damage, it continues from there onto the next page.

Yeah, the Mississippi Department of Archives has been my best source of images right now. Problem is, the Candlestick Park tornado was very likely not the same tornado that devastated Scott County to the Northeast. Both storms were very impressive and killed more than 20 people, but the Scott County storm is the one that supposedly scoured the ground and peeled pavement of multiple roads.

Pingback: The Indefinitive List of the Strongest Tornadoes Ever Recorded (Pre-1970): Part II |

There was a tornado in Kansas that was believed to be an F5 and over two-miles wide. It happened two days after the Sherman, TX tornado. It was May 17, 1896 . This tornado like I said was over two miles wide and on the ground for 100 miles. I believe it killed 25 people. It cut a path length all the way from Seneca, Kansas all the way up to Falls City, Nebraska. Do you know if there are any particular damage photos caused by this tornado?

There was also a tornado in Leedy, Oklahoma that happened on May 31, 1947 a month and a half after the Woodward, Oklahoma tornado on April 9, 1947. The tornado in Leedy also believed to be an F5 may have been more intense than the Woodward tornado. People during that time claimed the damage appeared to be more complete than even than done in the Woodward tornado. I believe cut a 1/2 to 3/4 mile wide damage path through Leedy. Another thing, I find this particularly odd, but it seems like your most intense tornadoes on average had a path width of 1/4 mile to a mile-wide? Of course some F5/EF5’s have been narrower and some larger but the most intense always seem to be in the 1/4 to a mile-wide range.

Someone recently posted some awesome pictures of the Leedey tornado aftermath on talkweather. Looks to have been a rather intense storm, regardless of its slow movement.

As for tornado width, there is so much variability in damage paths. For example, the Joplin tornado was deemed to have been 0.8 miles wide at its widest, yet the swath of EF3+ damage was more than half a mile wide. The Phil Campbell tornado supposedly reached a peak width of 1.2 miles wide, yet the swath of EF3+ damage in that area was only 150 to 200 yards wide.

I agree, however, that the most intense tornadoes generally are in the 1/4 to 1/2 a mile wide range, yet the zone of “extreme” damage in most of these tornadoes is much narrower, generally between 80 and 300 yards wide.

Do you happen to know the largest extreme damage swath created by extreme winds in a tornado?

You mean the largest swath of EF4+ damage? I’d say the ’97 Jarrell tornado left the widest swath of EF4/EF5 damage I’ve ever seen – homes were swept completely away over a path more than half a mile wide. The Joplin tornado was pretty wide too – the intense damage covered a much wider area than plenty of other storm’s with official path widths greater than one mile.

Maybe it’s just me, but just based on eyeballing tornado statistics, it seems that tornadoes east of the Mississippi (Tri-State, April 2011 tornadoes for example), seem to move faster than their great plains counterparts. Is there any particular reason for that?

Yes, because violent tornadoes east of the Mississippi (Deep South, KY, TN, IL, IN etc…) most often form in the winter and early spring, when upper level winds are stronger and storm systems move far more quickly. Summer-time tornadoes are often centered in the Great Plains and upper midwest (MN, WI, SD, ND) and generally move much more slowly and are more clearly visible due to less precipitation.

Oh I see. Thanks for clarifying that. I’ve spent quite a bit of time on your site lately, and have come up with some interesting stuff.

Another thing I’ve noticed, it seems that the wedge tornadoes are very infrequent in MN, MI, and WI when compared to other areas (Chandler, MN being an exception). The Hudsonville Tornado, for example, wasn’t very wide, but extremely violent. Barneveld was 1/4 mile wide at it’s widest, and Oakfield was even smaller. Is that just random, or is it not really known why, or could that also have something to do with upper-level winds, seeing as Wisconsin and Minnesota seem to get more violent tornadoes in June as opposed to May or April?

The narrow, slow-moving, funnel-shaped tornadoes in the northern Midwest in the summer are a product of weaker upper level winds and less ambient moisture, as well as more things I haven’t spent the time researching.

Obviously, the Tri-State tornado was an incredible meteorological event, but how long do you feel the EF5 damage swath was?

I have not looked as closely into the Tri-state event as some other historic tornadoes, but it sounds as though the storm (assuming it was one single tornado) maintained EF4+ intensity for the majority of its life, and very likely held E/F5 strength for 150 miles or more.

Curious, why did you take the 1923 Pinson tornado off the list? I’m guessing it happened so long ago there’s not enough evidence.

Correct, I was unable to find enough evidence at this time to keep it on the list. The same may soon be true of the Winston County tornado – it was clearly a powerful, fast-moving Alabama wedge but there are no photographs available (from what I’ve found) of EF4+ damage.

Extremeplanet, it’s amazing how much your site has changed the online dialog about tornadoes. Seems other sites are popping up that focus on historical tornadoes, unconventional damage indicators like ground scouring and vegetation damage, and new photos of the damage. Funny how I see the the term “stripped low lying vegetation” everywhere now. never saw that before you said it. Just thought some credit was due to you! Keep up the great work and please post some new tornado info.

What about the Tracy tornado? It threw boxcars more than two blocks and swept homes off their foundations.