*Please note that I only use peer-reviewed sources to draw my conclusions on Hurricane Camille’s intensity at landfall.

Hurricane Camille near maximum intensity on the afternoon of August 17, 1969. Sustained winds at this point were well into the category 5 range. The hurricane would soon enter a weakening trend and make landfall with winds under 155mph.

At top, view of a tied down mobile home in Pass Christian after Hurricane Camille. At bottom, the remains of a tied down mobile home in Cutler following Hurricane Andrew. A thorough study of wood framed structures following Hurricane Camille found only modest damage, with homes unaffected by falling trees having little to no damage. (Wood Structures Survive Hurricane Camille’s Winds)

□ The internet has prompted the rapid dissemination of information about the infamous Hurricane Camille. With 190 mph sustained winds at landfall and a storm surge over 22ft, Camille appears to be an unprecedented event. Myths and legends related to the storm, such as the infamous (and fictional) “hurricane party” at the Richeliue Apartments, have entered mainstream media and rewritten the history surrounding the hurricane.

Hurricane Camille was last intercepted by Hurricane Hunters more than 150 miles south of its final landfall point near Pass Christian, approximately 24 hours prior to crossing the coastline (NWS, 1969). While rarely mentioned, this final offshore flight suffered mechanical problems and failed to intercept the storm’s eyewall, so the data regarding pressure and windspeed was estimated in order to fill the chronological gap. No reconnaissance flights were flown into the hurricane thereafter, so the 190mph wind figure has no basis in direct observation. Reanalysis has concluded, however, that Hurricane Camille was not a category 5 at landfall.

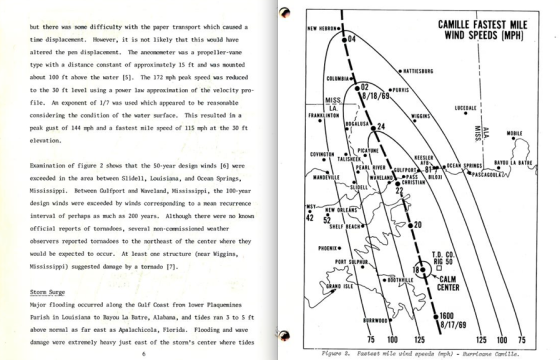

Hurricane Camille wind contour map showing maximum winds at landfall around 145 mph. Some meteorologists say these maps misrepresent hurricanes with multiple wind maxima like Hurricane Camille. Either way, it is certain that Hurricane Camille was well under category 5 strength when it crossed the Mississippi coastline.

A wind contour map published by NOAA reveals peak winds in Hurricane Camille were likely around 129 knots (148mph) eight miles east of the center. This release alone should have immediately led to Camille being downgraded to a category 4 storm, but no such action has yet been taken. The official NHC report on the hurricane actually says that “highest wind near the center were estimated at 160mph, with gusts to 190mph” at the time of landfall (NWS, 1969). In reality, the Mississippi coastline likely experienced sustained winds under 150mph.

The original NHC report on Hurricane Camille contains multiple inconsistencies. When mentioning the maximum sustained winds at landfall, the document never provides a definitive estimate. While the report mentions that damage in Pass Christian resembled “more the effect of a tornado than a hurricane,” aerial damage photographs show rather unremarkable wind damage. Strangely, the report also uses many “estimated” wind values whereas the NHC generally always uses only quantifiable measurements. Even more bizarre, the report does not mention multiple anemometer locations along the Mississippi coastline that were utilized in reports on other hurricanes that impacted the area in the preceding decade (it was standard for the reports to mention the maximum reading prior to failure when anemometers had incomplete data).

Coastal pine tree damage from Hurricane Camille near the area of maximum storm surge in Pass Christian. While it is commonly accepted that the storm’s landfalling pressure was 909mb, the circumstances surrounding the reading are questionable. St. Stanislaus College, located less than a mile away from the site attributed to the 909mb reading, recorded a minimum pressure of 944.8mb (Michael Laca, 2013).

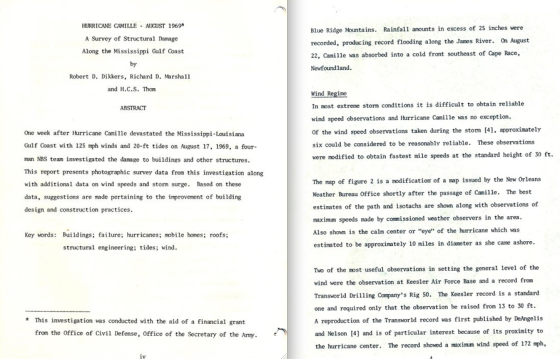

It appears that Hurricane Camille’s legendary status has protected it from being downgraded. There is no debate over the fact that the hurricane was a category 5 offshore. As it approached the coast, however, the hurricane’s winds weakened significantly. Surface reports are congruent with winds at landfall being somewhere in the category 4 or category 3 range. A Transworld Drilling Company rig, raised approximately 100ft above the ocean, recorded a wind gust of 172mph near the most intense quadrant of the storm before the anemometer’s paper tray jammed (the cessation of the trace was not due to the anemometer failing in high winds). A National Bureau of Standards survey adjusted the gust to 144mph at 30ft elevation and found the highest adjusted sustained windspeed measured was 115mph (NBS, 1971). While the rig’s reading is impressive, the measurement was taken more than 70 miles off the Mississippi coastline. On land, the highest officially recorded gust was 129mph at Keesler Air Force Base in Biloxi (NWS, 1969).

A 1971 NBS report which examined the damage from Hurricane Camille’s storm surge and winds concluded that peak winds at landfall were approximately 125mph. The report discusses the various wind readings taken in the storm and the inaccuracies contained in the NHC report.

Damage from Hurricane Andrew at the Deering Estate, just north of Cutler Bay. Trees in the area were stripped completely bare or leveled to the ground. Tree damage was equally severe well-inland in areas affected by convection cells in the southern eyewall, such as Naranja Lakes. The tree damage following Hurricane Camille was significantly less severe.

Further evidence of Camille’s lower-than-reported winds at landfall are photographs of the damage in areas that should have experienced the storm’s maximum winds. Hurricane Andrew in 1992 caused much more intense wind damage than Hurricane Camille. Both hurricanes struck at similar latitudes and both hurricanes encountered similar vegetation, so the comparison is very valid. In Hurricane Andrew, pine forests were stripped of all their branches and leveled. Photographs from Pass Christian after Hurricane Camille show rather unimpressive damage to the coastal pine trees.

Hurricane Katrina behaved much like Hurricane Camille did 36 years later. Like Camille, the storm reached category 5 strength in the Gulf of Mexico and, like Camille, it weakened before making landfall yet still brought with it a tremendous storm surge. Katrina was significantly larger than Hurricane Camille, however, and the resulting storm surge was higher and much more encompassing. Long time residents interviewed along the Mississippi and Alabama coastline universally considered Hurricane Katrina the worse of the two storms.

Two additional views of damage in Pass Christian, where Hurricane Camille’s most intense winds swept ashore. The condition of the trees and homes unaffected by the storm surge is inconsistent with wind gusts over 200mph.

Views of damage in Pass Christian. An extensive photographic survey of the area concluded that nearly all of the wind damage was caused by falling trees. At right, buildings near the coast in Pass Christian. The lower floors were destroyed by the storm surge, whereas the upper floors suffered little damage. (Wood Structures Survive Hurricane Camille’s Winds)

Severe storm surge damage framed by standing utility poles, fairly undisturbed trees and a hardly-damaged gas station awning. While Hurricane Camille is often described as being a “tiny” storm, it was, in fact, much larger than the two genuine category 5 hurricanes to impact the United States – the 1935 Labor Day Storm and Hurricane Andrew.

Data collected from researchers indicates that Hurricane Camille impacted the Mississippi coastline with surface winds between 120mph and 145mph. Radar images of the storm verify the development of two concentric eyewalls in the hours prior to landfall, a structural change which dramatically reduced the storm’s winds while only moderately increasing the central pressure. The extreme intensity of the storm in the hours prior to landfall, coupled with the heightened vulnerability of the Mississippi coastline, led to tremendous storm surge heights in excess of 20ft in a small area centered on the town of Pass Christian.

Unbiased damage and assessment surveys failed to find structural damage indicative of winds in excess of 160mph. The NHC preliminary report on Hurricane Camille contained various inaccuracies and is not an objective source of information pertaining to the storm. Satellite imagery suggests the storm may have reached maximum intensity on August 16th while located approximately 400 miles south of Mississippi. While it is unknown why the official report deviated so radically from the realities of the storm, analysis from the 1960’s both in the Atlantic and Pacific tended to overestimate hurricane intensity. The storm is an excellent example of how easily misinformation can cloud “official” analysis of hurricanes or tornadoes.

*Perhaps the best resource for full-color images of Hurricane Camille’s damage can be found on the Mississippi Department of Archives and History account here.

Nice job. I always thought the 160 knot landfall intensity seemed dubious. Glad it got changed to something realistic.

Interesting… but this report is incorrect. Multiple other resources verify the wind speeds at Stennis and Keesler AFB. Gusts were recorded at 229 and 230 mph. Even the NHC still verifies that she was a cat 5 at landfall. This report is not based on broader facts but limited sources who for whatever reason seeks to minimize the storms intensity.

“Gusts were recorded at 229 and 230 mph”

Where did you get such information? This report states gusts of 160 mph and 129 mph at Stennis (Mississippi Test Facility) and Keesler AFB respectively.

Click to access H_CAMILLE.pdf

My husband needs proof of being at keesler airforce base during camille. His name is george augustus nahm. If anyone remembers him there or has a pic of the units there just before please let me know. He was there on 8/8/1969 but records were lost

I was living about 90 miles north of the coast in Columbia, MS when Camille hit. I remember news reports coming from the coast indicating the winds were well over 200 mph at landfall. We reportedly still had winds in Columbia recorded at over 100 mph so it was definitely a very strong storm. And at this point, who cares what the actual wind speed was because it was a devastating hurricane. And I recall, we were on the back side of the storm so the winds on the front side would have naturally been much stronger.

We were stationed at Keesler, but had gone about 90-100 miles north to visit relatives south of Hattiesberg. We had the eye of the storm. The EYE, that far north. That part was amazing, because the wind stopped suddenly and completely, then started back up a few minutes later. It ripped the roof off our relatives home and the windows exploded. Again – this was many miles north of the coast. The wind was measure at more than 200mph at the coast, but the device broke at that point, so the highest gusts are not known. Our home (Harrison Court base housing) was on Back Bay, on a cliff – about 18 feet above the water. The home was on piles (at least 4-5 feet high, because the porch was above your head if you stood in the yard). We had 3-4 feet of water in the house. The entire beach area looked like a bomb hit it, for blocks and blocks inland. Chunks of Highway 90 (entire slabs of it) were lifted up from the sub-structure. An entire section of a railroad track was twisted into a spiral. There’s no way to describe it if you were not there. I trust the official information we heard directly from the USAF and the nearby Naval base. Keesler’s training buildings were designed to withstand hurricanes, and for those who sheltered there, they indeed protected people. By the way, using “peer reviewed” sources does not mean this article was peer reviewed. I teach at a university.

First of all, english is not my mother tongue so please consider that before reading this comment, I truly wish I could express my feelings better on this (I understand English well, but can not write or talk so).

Thank you for posting this, the most interesting reading on this subject yet for me, and the Michel Laca comment is a must see for everyone as he’s a real authority on this subject. Now after the official landfall intensity was reduced it’s clear that NHC took a conservative approach as a dramatic “lowering” of the landfall intensity would be considered disrespectful to the scientists responsible for the the earlier estimations (I understand their position, though I do not agree, as TRUTH should always be the main goal in the scientific area, and it’s easy to “forgive” the pioneers for the past errors considering both the less information and the less advanced technology available by then. The relatively minor tree damage alone (along the RMW area, documented by countless photos above the water line, and just out of the surge area) is enough to dismiss any chance of sustained (and maybe even 30 ft level gusts) cat 5 winds at landfall, and comparing Camille’s WIND damage photos to Hugo and Andrew’s photos makes this point bright as day. In recent years the global benchmark for a cat 5 landfall is Haiyan/Yolanda, and the southern parts of Eastern Samar (from Marabut eastwards, and mainly south of Quinapondan to the tip of Sulangan, where very little storm surge affected the populated areas [unlike the Tacoblan region, were winds were actually much weaker in the central area but the surge was higher]) was left barren as a desert, those were winds incomparably stronger, up to “upper cat 5” class. Another interesting (and underrated) typhoon was Rammasun in 2014, the tree damage in the sparsely populated NE part of Hainan island was very impressive, the few pictures available around the Wengtianzhen area (western/southern eyewall) are particularly interesting and I believe even the adjusted peak wind intensity estimation by JTWC might be a little low (and the lowest pressure estimation of 935 mb is surely too high), the southern eyewall then skirted Haikou city much weaker but still carrying a punch (but probalby cat 2 winds /3 gusts in the northern neighborhoods), what was frightening but weakened enough to avoid the major tragedy the city would have faced if it was built to the east. Sorry again, for my poor english.

I was 18 and have been through every hurricane through Hattiesburg Ms., 60 miles north of the Ms. coast since Camille. Katrina was the second worse a cat 3 @ 920 mbars wound very tight it decimated a 60 mile wide swath 80 miles inland. I watched 9 trees and a massive oak beside my driveway go down almost simultaneously. But it didn’t even come close to the terror of Camille for those of us who rode it out regardless of revised numbers. At landfall it was 900 bars second lowest on the Gulf only to Galveston 1937 said to be lower. It killed 259 people some in Appalachian flash floods. Much worse than Katrina, I was in a very large house and the entire structure felt like it was vibrating about to explode at any moment. There are hundreds of people who went through the same terrifying feeling from winds and tornados. Of all the hurricanes ridden out from ’69 to date, none even came close to the terrifying winds and destruction of Camille at 60 miles inland. “Rather unremarkable wind damage” is absolutely ludicrous. My father a lineman was there the 3rd day working and took me down one day. It looked like a small H -bomb was set off with 6 to 8 miles in was all but leveled structures and trees. The 3 story apartment building, people did have their hurricane party. I have a copy of the lady that survived and her statement on an old VHS tape. “Steps to Nowhere” documented the people that were there, title taken from that building where the foundation and steps were all that was left.

Sincerely, Dave

You are very correct!

I was 12 years old in 69 and my uncle and aunt lived in Pass Christain MS about 3 blocks off 90.on Davis Ave. I went to stay with them like I did for 2-3 weeks before school to enjoy the gulf and swim/fish with my uncle.

He had a 66 Impala SS that i loved and and 68 GMC truck with a camper. We watchd the reports on TV and if not for me im sure they would have stayed in the house and rode it out. We loaded up the truck and I stayed in the camper and left the night of Aug 16th to goto Mccomb MS were my Grand Parents lived and wait for the storm to pass. We tried to go back on the 20 but the National Guard kept us out.

My father came from Houston to get me on the 25 we made it to were the house was….nothing but a slab of cement. The 66 chevy was never found. My aunt found one pot from her house and that was it My father was in the army and had seen the “The Bomb” in Japan and said the area looked just as bad or worse…. like a small h-bomb went off. tankers washed up 5 miles inland etc, I still have some old 110 ics i took on aug 27th. I went back one year later and it still looked like bomb had gone off. The next time I returned was 1974 …..5 years after and the signs of the storm were still very much still there. Im sure If we would have stayed put I would not be typing this tonight.

Pingback: ‘The 1999 Bridge Creek Tornado was the Strongest Tornado Ever’ and Other Misconceptions | Extreme / Planet

Camille was definitely a cat five I know this because I lived through it pressure at landfall was 905mb much stronger than Andrews it broke the wind gauges at stennis space center with gusts of 218 mph no cat 3 has ever done that 100 miles inland it was still a cat 3 storm I have been through many cat 3 storms most recently Katrina where my home was lost and Camille was the only one that sounded like a freight train it was terrifying so I don’t know where your info comes from but it false

The highest reported wind gust from Hurricane Camille was from an offshore oil rig that recorded a wind gust of 172mph, according to the official NHC report linked below. The platform was about 100ft off the ground, I believe, so the ground (or ocean) level winds would have been less. There are no official, or unofficial wind readings any higher than that, just internet legend.

The highest official gust recorded on land was 129mph, also according to the official 1969 report.

*I have added these details into the post.

Click to access TCR-1969Camille.pdf

Arguing that “____ was definitely of intensity ____ because I lived through it” is among the weakest evidence available. Although potentially helpful in the absense of other objective information, such anecdotes are not particularly strong.

I would imagine that Camille will be re-analyzed by the committee similar to how Andrew was and they may share your opinion. The H-Wind data was used in the Andrew re-analysis to help determine the increase to Cat5.

I agree. I own a few books written with articles that are from people who lived through it, and anyone trying to degrade Camille’s intensity is foolish. The Richelieu apartment story is NOT fake. Hurricane Andrew is just a rain squall compared to this moster.

Why is someone looking at official figures released by the NHC foolish? I don’t understand the extreme emotional response this article causes.

The only evidence I use in my article is data from official sources and peer reviewed research articles, all of which indicate the storm did not cross the coastline with category 5 winds.

I just noticed I got a good deal of traffic from wunderground, where several members claimed that “sustained winds of 212mph” were recorded. I would love for someone to point me to the source of that information because the NHC and local organizations kept extremely meticulous records following the storm, and the highest wind gusts (official and unofficial) are the ones’ I mentioned.

And the Richelue “hurricane party” story has 100% been proven false. Please make some effort to google information before spreading claims that are completely untrue.

If anyone disagrees, please show me ONE shred of evidence (either real anemometer readings mentioned in an official source or damage photographs) that indicate the storm had category 5 winds. You’d think there would be at least ONE photograph from the extensive imagery following the storm that showed extreme wind damage consistent with cat 5 winds.

From the 1969 Monthly Weather Review: “During the night and morning of August 16 and 17, no further penetrations of the hurricane were obtained, although a Navy reconnaissance plane circumnavigated the storm at low levels and reported winds substantially in excess of 100 knots at a radius of 30-40 mi from the center. Early on the afternoon of Sunday, August 17, an Air Force WC-130 reconnaissance plane once again penetrated the storm. The hurricane at that time was less than 100 mi from the mouth of the Mississippi River. The crew estimated the highest surface winds to be 180 kt. During this penetration, the aircraft was forced to feather an engine and had to leave the storm area so that no further reconnaissance data were obtained until the storm crossed the coastline.”

That’s verbatim from the text. That same crew estimated a SLP of 901, down from the official 905 measured earlier. Pressures were still falling when the plane was forced to leave. An amateur observer in Pass Christian measured a 200 mph gust before his device failed. I assume those are the reports you’re dismissing. A 105 knot sustained wind was reported in Columbia, Mississippi – 75 miles inland. That reading has been confirmed. The storm had been onshore for approximately 8 hours by the time the center reached Columbia.

The lack of data doesn’t mean it was weaker. There were no wind instruments in the eyewall that survived the storm, so will never know. Camille was a very small hurricane (even smaller than Andrew I think.) There would be a sharp fall-off in wind the farther you went from the center. The comparatively small damage in Biloxi means little. Food for thought: how did a small, fast-moving storm like Camille get a 24.2 foot storm surge? And that’s just the official reading. So much was destroyed that we don’t really know how high the storm surge was. Estimates run as high as 28. Andrew’s was 17 and it was slower and had been over water longer. How could a 130 knot Camille get that much kinetic energy? Do I know Camille had 200 mph winds at landfall? No I don’t…no more than you know it had 150. I expect HRD will have a structural engineer analyze the photos when they reanalyze Camille. But there’s only so much you can learn from small, grainy 40 year old photos of often unconfirmed locations relative to the track.

Do you have sources for the 200mph unofficial wind gust and the 105kt sustained wind in Columbia? I just did a google search and was unable to find those readings anywhere, including scholarly sources.

My approach to analyzing things, as mentioned throughout my site, is via what I consider completely objective means – that being damage photographs and reliable measurements/reports. Photographs are available of the entire Mississippi coastline following the storm – high quality, color pictures linked in the article above. The wind damage was far less intense than that caused by other intense hurricanes (Andrew, Carla, Labor Day, Charley). Additionally, a detailed study of the damage that covered the entire coastline (linked above) concluded that very little wind damage occurred besides falling trees. If that doesn’t make someone suspicious about the winds, I don’t know what could.

Yes, the lack of wind damage in Biloxi may be the result of the storm’s small size, but the lack of severe wind damage on the coast in Pass Christian/Waveland (“ground zero”) is not explained by that. The trees and buildings were not covered up by storm surge as some have suggested or else they would have been severely damaged or destroyed.

As for the storm surge, Hurricane Katrina recently taught us that the intensity of a hurricane in the hours prior to landfall can dramatically affect the recorded heights. Also, you drew a comparison between Hurricane Andrew and Camille in terms of size. Camille was more than twice the size of Andrew – with hurricane force winds extending 60 miles as opposed to 25 miles from the center respectively. So Camille was not tiny, and it struck the most sensitive area in the entire US in terms of storm surge potential – so a 22ft storm surge in a weakening cat 5 hurricane with sustained winds of 145mph makes perfect sense. The storm also had two concentric eyewalls at landfall, which reduce wind speeds in relation to pressure.

Also, everyone seems to overlook the NOAA wind contour map which I posted. The only wind contour map available of Camille- which was made using modern analysis techniques from the single most official source for weather information – shows landfall winds of 140 to 145mph.

The 105 knot sustained wind reading from Columbia comes from the 1969 Monthly Weather Review: http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/general/lib/lib1/nhclib/mwreviews/1969.pdf (the table on page 8). They also note that the anemometer failed when it reached that point, so it may have been higher. Gusts to 115 kts were also measured. It’s also worth noting that small storms tend to weaken much quicker as they move inland (Charley dropped three categories in just a few hours).

As for the graphic, they used what, exactly, to derive it? There is no data to tell us exactly what the intensity was. There were no wind or pressure readings from inside the eyewall at landfall.

You can’t make a determination on the intensity of winds by looking at trees in 40 year old photos (most of which were focused on something else). It’s no different than looking at a picture of a clean slab after a tornado and calling it an EF5. Context is important. Age of the tree, soil quality and depth of root systems are all important considerations. Consider this, Mississippi hadn’t been hit by a big hurricane in decades. Those trees were old and dug in. I’ll wager they were stronger with deeper root systems than the trees felled in Andrew.

Could Camille have been weaker? Absolutely it could’ve. I doubt that Camille had 200 mph winds at landfall. That said, based on recon data, I do believe that Camille probably had winds close to 200 mph as little as 12 hours before landfall. The rate of weakening though with the Columbia reading suggests a landfall intensity higher than 130 kts. The idea that a storm the size of Camille only weakened 25 knots after spending 8-10 hours over land just doesn’t seem right to me. The much larger Katrina weakened about that much in maybe six hours.

And I still believe that Camille had to have achieved and maintained a very high intensity to have generated enough kinetic energy to produce a 24.6 foot surge. Chandeleur Sound does facilitate surge somewhat, though not as much as the concave coast of the western Gulf. Gulf surges do tend to be higher than Atlantic surges because of shallow water. But I just don’t get how a storm half the size of Katrina, moving about twice as fast, hitting almost exactly the same location could produce a storm surge just a few feet shorter without having extremely high wind speeds. That energy has to come from somewhere.

I just read parts of that article and, well, there are mistakes. Camille was not the costliest hurricane in US history at the time, Betsy was (though they were close so thats ignorable). The highest recorded storm surge height listed is wrong. Figure 3. claims the storm surge in Biloxi was around 20ft, which is totally inaccurate. It says homes within 100 yards of the coast were swept away by winds similar to intense tornadoes when, of course, the surge did that – and views of the entire coastline (Waveland, Pass Christian etc…) do not show that at all.

As for the Columbia reading they have – it’s strangely well rounded for an actual reading (120mph/gusts to 135mph) with an unusually low gust ratio. Likely they simply put in another “estimated” reading by mistake as that measurement appears nowhere else – not the official report, not newspapers in the area, not any peer reviewed sources I’ve found.

As for the wind damage, a lack of any hurricanes in the previous decade would leave trees more vulnerable. Betsy also brought winds over 100mph to the MS coastline a few years earlier. Additionally, the pictures don’t just show trees with little damage but buildings with very little damage. Having gone through literally every image (I, like you, once believed it had cat 5 winds at landfall) the worst damage I found was a motel that lost its roof and a section of its upper floor, military hangars that were nearly ripped apart, and a home that lost its whole roof. And that’s after looking at hundreds of high quality aerial/ground level images of the coast. Camille isn’t dictated by different rules – every other hurricane making landfall in the northern Gulf left damage consistent with the official intensity, but not Camille.

As for the NOAA contour map, it’s based on the available anemometer readings/pressure differentials and other things I am too lazy to look up. The graph also does not account for the storm’s concentric eyewalls, a characteristic which always leads to a weakening of storm winds. I have never heard of a cat 5 hurricane with concentric eyewalls – its universally a sign of weakening.

I have always said that my mind could easily be changed if someone showed me a picture of extreme wind damage – and none of the dozen people who have e-mailed were able to do so.

The MWR is a peer-reviewed science journal sponsored by the AMS and the data was compiled by NWS meteorologists who were actually there looking at it. How do you know the info’s wrong? Where are your sources? These guys were there studying the damage in real time, therefore, I trust them more than I trust your retroactive photo analysis.

The Monthly Weather Review is considered more accurate than preliminary reports because it includes more data. These days, the issues simply reiterate NHC’s post-season reports, but back in Camille’s time there definitely was a difference. The post-season reports were called “preliminary” for a reason. And, for the record, I see no evidence of anyone claiming 150 mph winds in Biloxi. The MWR gives highest winds at Keesler as 67 in gusts. Pascagoula was 81. The highest wind readings on land were inland. Highest coastal reading was a 107 gust at Boothville, LA.

Also keep in mind that Hurricane Andrew was able to maintain high intensity over populated areas well past the storm surge inundation zone because it passed over a low friction land mass. Camille moved over a high friction land mass and would’ve lost strength sooner. It’s unlikely that structures much outside of the inundation zone would’ve experienced the extreme winds. Therefore the damage from wind and surge in Camille is difficult to distinguish. In Andrew, it was easy because the surge was irrelevant.

The surge damage in Camille was some of the most incredible I’ve seen in nine years of studying historical hurricane events, based on the character of the buildings destroyed. A substantial, multi-story apartment complex and a large, antebellum mansion were among the buildings that were utterly erased. I’ve never seen large, well-built structures so completely obliterated like that by a hurricane. It’s been widely speculated that extreme winds facilitated these collapses. Also note the extensive tree damage around those two structures, but again it’s impossible to distinguish wind and surge damage along the coast with so few surviving structures.

I never asked you to take my “retroactive photo analysis” perspective over a published report, but my data comes from the official NOAA wind contour map (hard to say that is not an “expert” source), a very thorough, objective wind damage analysis article (linked in the entry), the imagery of the damage and the opinions of my three primary hurricane chaser friends/chase partners (all of whom are well respected in the community – but I don’t wish to bring them into this debate).

Camille made landfall in a completely flat place, just like Andrew. Like any hurricane, the damage would be evident within the storm surge zone (the upper floors of buildings that survived generally had all their windows and their roofs in tact, as discussed in the analysis article) and immediately beyond that.

In the end, there is evidence for both sides. I prefer what I consider “objective” evidence, meaning actual measurements, unbiased damage analysis and photographs. I believe the official analysis, like many in the 60’s in the Pacific and Atlantic, was wrong – and since then everyone has tried hard to “protect” the storm’s legendary status. Check out forums and youtube entries – people get enraged when the intensity is questioned and make-up measurements – such as a 212mph (some say 250mph+) gusts/sustained winds recorded before failure at a military base/pier/whatever the person decides at the moment.

I chase hurricanes/tornadoes and survey damage, so I have a pretty solid understanding of storm analysis. Not saying I know better than others, but I am rather surprised people believe the storm’s landfall intensity despite proof that there was only moderate wind damage on the coastline. Part of becoming a researcher is learning there is both conflicting and flat out wrong information out there, plenty of it actually, even in “official” sources.

Again, I want someone to come back at me with ONE picture that shows wind damage consistent with cat 5 winds (there are literally hundreds of high quality images linked above of the entire Waveland/Pass Christian coast. Because if people believe that’s all that a storm with 190mph sustained winds can do, they are in a for a bitter surprise.

I am a semester away from having a bachelor’s degree in meteorology and have been studying historical hurricane events for nine years, so I’m hardly blowing smoke (nor am I accusing you of saying that).

The bottom line to all my arguments is that there’s not enough conclusive evidence to support one way or the other (something I think you’d agree with). The thing is though, a lot what you’re referring to as “objective” is in fact “subjective.” Photographic evidence, for example, is subjective. Forty years hence, we have little info on the context of that damage.

The SLP measured in Bay St. Louis at the west end of the bridge was 909 millibars (26.85 inches). That’s official, straight from the MWR. In the Atlantic, the lowest pressure ever recorded in a landfalling hurricane with winds less than Category 5 was Katrina’s 920 mb. The lowest pressure ever recorded in a Cat 4 was Wilma’s 901 mb during its weakening phase (pressure tends to lag winds during weakening, reverse of strengthening). Wilma was a very large, deep, monsoon-type hurricane, a vastly different structure than that of Camille.

Pressures in smaller storms tend to be higher than in larger storms of the same intensity, except during rapid intensification when winds lag the pressure. I haven’t done the math, but I’ll bet the wind-pressure relationship for a storm of Camille’s size would be higher than 130 knots. Probably not 165, but higher. WP relationships are hardly an end-all-be-all, but they’re certainly more objective than looking at pictures.

And with the offshore rig reporting 172 mph @ 100 ft (probably 160-ish at 10 ft), and the 120 at Columbia 6-8 hours inland, I see little evidence other than photographs to support Camille being anything less than a Cat 5 at landfall.

I contacted my good chaser friend who sent me an NBS article created by a joint effort of the Army and Civil Defense in 1971. They thoroughly analyzed all of the structural damage from wind and surge and concluded peak winds were 125mph at landfall. The 172mph gust (mentioned in the report) was lowered to 144mph at 30ft elevation – and the report said the paper tray jammed – so the anemometer didn’t fail due to the winds. The highest adjusted 30 second sustained wind recorded by the rig was 115mph. I attached the first four pages of the document in the article above. The survey was objectively looking at how building codes could be strengthened, so the only interest was in ascertaining the actual wind velocities vs the sensationalized reports.

I was only sent the first 10 pages via image files, I’ll have to look and see where I can find the whole document.

Either way, if the pressure is the main thing making you think the winds were cat 5, look into concentric eyewall development.

Looking at pictures might be subjective, but reading peer reviewed articles written by meteorologists/engineers at the time who examined the damage and meteorological measurements is about as objective as you can get.

It just doesn’t make sense for a storm with Camille’s structure to have a pressure that low and not have Category 5 winds. It would be nearly unprecedented for a storm with any structure, much less a small storm. Concentric eyewall formation has little to do with it (I’m actually doing a directed study on concentric eyewall formation as it relates to RI). Katrina’s pressure, like Wilma’s, had much more to do with storm structure and pressure gradients. These allowed Katrina to maintain a very low pressure even after its inner core was disrupted by an ERC and land interaction. Katrina’s pressure also rose 18 millibars between peak intensity and landfall. Camille’s rose maybe 8 millibars from peak intensity to landfall (and that’s if you use the unofficial min of 901).

When a storm undergoes an ERC, pressures begin to rise almost immediately, then the winds begin to fall off as the storm’s local pressure gradient relaxes. Pressure data available for Camille is inconsistent with a storm undergoing an ERC, but rather indicates a more gradual weakening. At the same time, just to play devil’s advocate, it would be unusual for a storm of Camille’s size and intensity to have not undergone an ERC. Storms like Camille are prone to rapid intensity changes, often rapidly intensifying before undergoing an ERC. Phases of gradual weakening without an ERC are somewhat out of character. That said, based on the available pressure data, that seems to have been the case with Camille.

I see no evidence in the objective data that is inconsistent with a Cat 5 landfall or any indication that Camille was undergoing rapid weakening at the time of landfall. Frankly, I don’t even know what NBS is. The MWR report was written by none other than R.H Simpson, THE Simpson who helped develop the Saffir-Simpson Scale, and his team. He is to hurricanes what Dr. Ted Fujita is to tornadoes. The evidence better be pretty darn good for me to say that he was so glaringly in error.

And I guess that’s where we will agree to disagree. I feel like people are saying “it must have been a cat 5 because of the pressure etc” and I am saying “I understand that, but what actually happened was the storm failed to leave a single indicator of cat 5 intensity on land.”

I am with you, the pressure and size scream cat 5 intensity to me. But the thing is, it simply wasn’t. That’s all I have the strength to say anymore.

Yes, Camille was a strange storm that left many mixed messages. So we can leave it at that – you believe the meteorological data used in the NHC report (from very reliable sources, I do admit) and I’ll believe the ground damage surveys.

Oh, the NBS is the National Bureau of Standards, what was the largest structural engineering entity in the world – basically the combination of both the military and the government in regards to building codes.

To me, it’s like the now resolved Hurricane Andrew debate. The hurricane hunter measurements meant the storm could not have been a cat 5 at landfall and yet the damage indicated otherwise.

You are 100% correct this was a monster storm by ALL accounts! The person that posted that the houses were swept away by the storm surge is an idiot! I was there and witnesses the damage first hand!!! A storm surge doesn’t live a whole house up and land it somewhere else where it looks almost like it was built there! This storm had tornadoes within it and a LOT of them! The wind meters were blown away and therefore there were no accurate readings! To look at 40 year old pictures and assume stuff is idiotic. This article is much more accurate! It definitely WAS a Cat 5 hurricane on landfall!!! Here’s some REAL facts: http://www.wunderground.com/hurricane/surge_details.asp

This is complete BS I was THERE! It definitely WAS a Cat 5 hurricane on landfall!!! The winds were so high they couldn’t even record them because the wind meter blew off! BTW I don’t know where he’s getting his “facts” from but here’s some REAL facts: http://www.wunderground.com/hurricane/surge_details.asp

I was in Camille as well and it was definitely a cat 5!

“Camille was definitely a cat five I know this because I lived through it pressure at landfall was 905mb much stronger than Andrews it broke the wind gauges at stennis space center with gusts of 218 mph no cat 3 has ever done that 100 miles inland it was still a cat 3 storm I have been through many cat 3 storms most recently Katrina where my home was lost and Camille was the only one that sounded like a freight train it was terrifying so I don’t know where your info comes from but it false”

Did you even read the article? It cites every piece of information used. And funny enough, you are exactly the kind of person referenced who makes up information.

The 218mph wind gust you completely made up – as if that couldn’t be proved false with a five second search.

And I find your vernacular and lack of punctation interesting because if you, in fact, “survived” the storm, then you would be at least in your 50’s to have a clear memory of it, or your 60’s if you were over 17 when it occurred. Yet I have never seen someone that age write the way you do. Makes me think you might be a younger person with a special fondness for the storm trying to pass off false information.

You need more to do with your time. Perhaps unicycling?

I have arrived at your blog yet again, this time via Jeff Masters blog.

I have to agree with you regarding Camille, particularly since the NHS updated the storm contour map showing much weaker winds at landfall. It’s rather irritating that people keep making up anemometer figures and fail to cite sources. Reviewing all of the damage photographs I have seen, I’d say the wind damage looks similar to other low-end category 4 hurricanes.

Of note, the platform that recorded the 170mph gust was 60 miles off the Mississippi delta, so even farther away from the Mississippi coastline.

I agree with your agreement, JW.

Do you have a source for the location of the oil rig being 60 miles off the coast of the Mississippi delta (I assume you mean the bottom tip of Louisiana)? I remember I found the name of it and discovered it was just about level with the tip of the delta but offshore to the east, but I’d have to dig to find it again.

Camille was a compact, intense storm, similar in that way to Andrew, which was like a small buzzsaw when it moved over south Florida. Andrew’s damage seemed to indicate the presence of small tornado-like intense wind vorticies, a lot more like tornado damage than the typical hurricane. Also, Andrew was a “dry” hurricane, caused very little flooding, it was basically strictly a wind hurricane. If it had been a larger hurricane, no doubt it would have picked up a lot more water. I remember Andrew very well and the neighborhoods in Homestead looked like a tornado had hit them. Very intense severe damage. And very widespread. It took them years to upgrade Andrew to Category 5, but it truly was a Cat-5 storm, it broke the NHC’s wind instruments when it passed over.

The question is whether to consider barometric pressure more, or sustained winds or just the occasional gust more when assigning intensity ratings for hurricanes. For instance, if the hurricane’s winds die down a bit, as it cycles, doesn’t it take longer for the pressure drop to catch up? So maybe Camille was cycling down as it hit land, and the very low pressure simply hadn’t caught up yet? And as far as the wind,speeds, if it was just a gust as opposed to sustained winds, etc.. Hard to say since Camille hit before very sophisticated measuring instruments had come into being.

Katrina was a very powerful 175mph Cat-5 in the Gulf shortly before landfall, but as we know, it dropped to strong Cat-3 upon landfall with Cat-4 gusts. But the barometric pressure and storm surge were in Category 5 range with Katrina. Of course Katrina was much larger than Camille & Andrew, and Katrina was a very “wet” hurricane that caused more damage via storm surge than winds alone.

Bottom line I think the jury’s still out on Camille, but I’m not ready to discount it being Cat-5 yet, but I think it’s indisputable that Labor Day 1935 & Andrew 92 are more solidly Cat-5s than Camille.

Hurricane Camille was actually not a “small” storm, it was rather typical of major hurricanes that impact the northern gulf coast. It was smaller than Katrina, but far wider than Andrew.

The hurricane chasers and meteorologists who I know all agree that Camille did not make landfall with category 5 winds. The wind contour map published by NOAA five years ago shows that the official landfall intensity, using modern analysis, is 145mph.

Someone of an ironic situation, given that Andrew was operationally assessed as a 145-MPH Cat 4 in the last advisory issued prior to landfall, and that’s what it was known as throughout the ’90s when it was the most destructive hurricane in recent memory.

On the topic of Camille’s intensity, I’ve definitely reviewed and analyzed a significant amount of information, from many different sources over the years and ultimately took the approach of trying to work backwards from the visually observed impacts, rather than looking solely at empirical data from recon or point observations and making all my assumptions from those (which I think happens all too often). Trying to be as scientifically objective as possible, I much prefer to look at all available information holistically, then put the most weight on whatever data has the most reliable, consistent and irrefutable attributes and then let that be the litmus test I hold any other available data to.

With that said, my personal thought is that Camille’s current landfall intensity of 165kt (190mph) in HURDAT is ridiculously high, which seems to be the sentiment among the majority of people I know in the meteorological community. Personally, I’ve never found any evidence to suggest winds anywhere near that intensity were experienced on land with this storm. Based on everything I’ve researched through the years, my personal conclusion is that Camille made landfall with sustained winds around 125kt (145mph) and a minimum central pressure between 935-937mb.

To adress some of the specific questions pertaining to key observations in Camille, which have formed the basis of my conclusion:

The 909mb (26.84in) landfall pressure was indeed “reported” as a surface measurement made near the west side of the Bay St. Louis bridge though,

unfortunately, no specific details on who made the observation, the exact location, the type of instrument, whether it was calibrated (or tested in post-analysis) has ever been given… which, considering the rigorous standards that other extreme observations are held to today, makes this observation, as it currently stands, somewhat unqualified.

Even more interesting, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Report on Camille from May, 1970, also cites the 909mb value near the “west end of the Bay St. Louis bridge” and actually goes a little further by saying “As Camille moved inland shortly before midnight Sunday, the lowest land pressure of 26.85 inches was recorded at Bay St. Louis a few blocks from the west end of Bay St. Louis bridge.” As with other publications, it’s unclear what source the original observation value came from, or how the location was identified as a “few blocks” from the bridge, unless there’s additional details about this data that someone knew about at some point, but no one has ever gotten around to including in any of the documentation?

More importantly through my research I’ve also found a few other pressure readings that aren’t commonly reported. The most important one being from St. Stanislaus College, which is also in Bay St. Louis and apparently had two barometers (one a recording barograph)… the barograph’s bottom limit was apparently 29.00in (982mb) and, after the pen went off the paper, the observer apparently continued making observations on a back-up instrument (though the description doesn’t say what kind, make, model, etc…). The lowest observed value from this second instrument was 27.90in (944.8mb) at 11:50 pm, which would have been just prior to midnight at approximately the time Camille’s pressure center crossed the coast. Even more amazing is that St. Stanislaus College is located at 304 S. Beach Boulevard in Bay St. Louis, which is literally right on the shore approximately 12 blocks south of the west-end of the Bay St. Louis bridge! This just seems extremely coincidental to me and I find it hard to reconcile an, as yet, unqualified 909mb value from virtually the EXACT same location. To be fair, the report also indicates that the time of the St. Stanislaus reading was “estimated” at 11:50 pm… but I think that’s beside the point… I’m much more open to accept a variance in the exact time of that reading, than to accept that the observer there didn’t notice the pressure falling another 35mb!

Additionally, a ship (the S.S. Alamo Victory) at harbor in Gulfport, 10 miles east of Bay St. Louis, recorded a minimum of 28.60in (968.5mb). In Biloxi, 18 miles to the east, the lowest pressure was 29.12in (981mb) at 11:55 pm . Given the wind damage I’ve seen, I’m much more inclined to believe a gradient of 24mb over 10 miles (or 36mb over 18 miles)… than 60mb over 10 miles (or 72mb over 18 miles). Even going farther inland, 50 minutes after landfall the lowest pressure at the Mississippi Test Facility (near Picayune, 13 miles NNW of Bay St. Louis, and near the path of the center) was 28.06in (950.2mb); and seven hours later at Jackson, MS the lowest pressure was 28.93in (979.7mb) which, assuming an average decay rate, seems completely reasonable from a storm with a landfall pressure in the upper 930’s to lower 940’s (I’m assuming that the 944.8mb at St. Stanislaus wouldn’t have been the lowest pressure, since Camille’s exact center came onshore approximately 2-3 miles west of Bay St. Louis, near Waveland… which would likely yield a landfall pressure somewhere between 937-940 mb.)

And, just to reitierate this even more, as early as 5:55 pm on the 17th, as the center was just crossing North Pass on the extreme eastern end of Blind Bay, Louisiana a minimum pressure of 27.80in (941.4mb) was reported at the Garden Island Bay Plant on Dennis Pass, which is only about 6 miles west of the track of the center… assuming the gradient derived from the landfall pressures above, a 24 mb drop over 10 miles yields a linear gradient of 2.4mb/mile (I know the gradient wouldn’t be truely linear, but just for arguments sake)… applying that to the Garden Isle Bay Plant value would yield a minimum pressure approximately 15mb lower…or about 926mb… which sounds totally plausible. Assuming the possibility of the ridiculously steep 60mb drop over 10 miles, at 6mb/mile that yields a minimum pressure 36mb lower than at the Garden Isle Bay Plant, or approximately 905mb… which is definitely close to what was being given as the central pressure at that time. But, this last reconnaissance flight was cut short (due to the loss of an engine) with the both the maximum winds and minimum pressure “estimated” (I cover this in more detail below). Either way, the minimum pressure the flight reported was subsequently corrected to 905mb in post analysis… and is exactly the same value from the previous night’s mission, which just seems really odd. Small storms with extremely low pressures rarely hold on to those extreme values for an extended period of time (especially northern Gulf landfalls, which almost always seem to weaken)… however, putting aside the wind estimates for the moment, taking the reported central pressures at face value, this would have us believe that Camille maintained a pressure between 905-909mb (a variance of only four millibars) for approximately 17 hours…from 5pm on the 16th through landfall at midnight of the 17th. For a northern Gulf storm, with a relatively small core, at an extreme intensity, that had an increaing interaction with land for the last eight

hours of that period… maintaining an almost perfect steady-state would be an incredible feat in itself.

The highest officially recorded wind (near the coast) was at Keesler AFB in Biloxi (likely outside the RMW), with a sustained value of 81mph and a peak gust of 129mph. A more impressive observation was made well inland at Columbia, MS with a sustained value of 120mph and a peak gust to 135mph at the time the instrument failed. The observer estimated the peak value was closer to 140mph. That said, there is little visual evidence to support that the Columbia observation accurately represents a “reduced” value of Camille’s ambient core winds. I would estimate that, with an averge decay rate from what I suspect Camille’s landfall intensity was, sustained winds in Columbia could easily have been in the 80-100mph range. So while, it’s not impossible that the 120mph observation represented the storm’s ambient core winds at that time, given the obvious lack of extreme wind damage from coastal locations in Mississippi and points inland, I’m much more inclined to think that the Columbia observation is a result of some other process, possibly a more localized downburst related to a collapsing precipitation core which we now know to be fairly common in landfalling/decaying storms (Ivan and Katrina being two more recent northern-Gulf

examples), and especially prevalent in storms with open-eyewall structures, which Camille also apparently had at landfall. Columbia’s observation aside, in my opinion, the most important (though unofficial) wind reading came from the Trans-World drilling rig #50, east of the mouth of the Mississippi river, which was located about 7-8 miles east of Camille’s center, and was almost perfectly situated within the RMW, in the right-front quadrant, during the storm’s closest point of approach to that location. Contrary to popular belief, this anemometer survived the storm and recorded a peak gust of 172mph, which is extremely impressive in itself… however, the platform elevation of that anemometer was 30m (100ft). So, a reduction of the Trans-World observation to the standard 10m (33ft) elevation yields a 144mph gust, and a fastest mile speed of 115mph… and this was from a completely marine exposure!

The National Bureau of Standard’s report on Camille (March, 1971) covers the Trans-World observation and others in detail and it’s obvious from a few of the comments of the authors that, even immediately after the storm, there were already questions about the legitimacy of some of the wildy high wind reports. Two quotations of particular intereset to me being:

“Spectacular estimates of wind speeds have been presented in a number of reports and articles on Hurricane Camille with little consideration given to type of exposure, height of observation and instrument characteristics. In reviewing hurricane reports submitted after the passage of Camille, approximately six observations of wind speed were considered to be reasonably reliable. Most of these required some adjustment to standard height and conversion to fastest mile. This lack of reliable information is quite remarkable considering the advanced warning of the hurricane’s path and the number of major installations with wind measuring equipment in the storm area.”

“The 100-year design winds (105 mph) were probably exceeded over the central half of this area. Though the true severity of Camille will never be known, it is interesting to note that the reported design speed of 150 mph assigned to the Mississippi Power Company building corresponds to a mean recurence interval of approximately 370 years. As noted previously, this structure suffered relatively minor damage.”

This report concluded that, in the area of Pass Christian, maximum winds were from the east with fastest-mile values “probably in excess of 140mph.”

Empirical data aside for the moment, a more important aspect to my research, has been a direct comparison of wind impacts to vegetation from Camille vs several other extreme TC wind events. In all of the imagery I’ve reviewed, there’s extensive to severe tree damage, but not on par with say Andrew’s impact in southern Florida. And, actually when comparing Camille’s impact to the region’s vegetation, I normally use Hugo in South Carolina as the best analog. Both Camille and Hugo made landfall at roughly similar latitudes and the vegetation in the two locations are very similar, slash pine, cabbage palms and other deciduous trees common to the southeastern United States. And, even with Hugo’s 120kt (140mph) winds, the tree damage, especially in the Romain Retreat area of Bulls Bay, is totally off the scale compared to Camille’s impacts. With Camille, once you get back a couple of blocks from the shore, beyond the area inundated by the surge, the tree line is surprisingly intact, even in areas traversed by the RMW, not to mention buildings with little to no external damage, not even shingles removed. Even structures that are within the inundation area from the surge (that survived collapse) have their lower portions completely

gutted, but the portions above the surge height don’t appear to be impacted that badly. This is graphically illustrated in the comparison photos in the gallery I have posted.

Another point which seems to come up fairly often during the re-analysis of these storms, are the inaccuracies that stem from non-standard reporting methods accepted years ago. In many of the storms in the 50’s and 60’s, flight-level winds from recon were often reported as peak “surface” winds without any reduction… and in the case of Camille, the last recon flight (which was 15 hours prior to landfall) “estimated” surface winds of 190kt (219mph) which is insane since winds of that magnitude would be virtually impossible to estimate visually from flight-level, not to mention that this flight had a mechanical problem and had to cut the mission short, without ever actually making an eyewall penetration! That flight also extrapolated a minimum pressure around 905mb, but again this was not a direct measurement. In the post-analysis, the 190kt figure was corrected to 165kt… but it seems like that this was done just to keep some continuity with the extrapolated pressure and, in my opinion may have actually reflected “flight-level” winds, instead of “surface” winds. In any event, the last direct measurements by recon were 24 hours prior to landfall and there is no questions that, at that time, the storm was at category five intensity. As a matter of fact, I think it’s possible that Camille was even stronger than the 902mb that that mission observed… but, it also seems highly unlikely that the storm would have been able to maintain that extreme intensity and remain almost steady-state for the following 24 hours. My guess is that weakening was already underway at the time of the last recon flight and, with the mission being cut short, they never got to sample the storm’s actual intensity at that point.

What has been documented about the last couple of reconnaissance missions prior to landfall indicate that on the afternoon of the 16th, a C-130 measured a minimum pressure of 908mb but was unable to measure maximum winds. Later that evening, the plane measured a minimum pressure of 905mb and maximum flight level winds (at 700mb) of 140kts (at a radius of 20 miles from the center)… the crew reported maximum winds were not measured due to attenuation problems with the radar. On the morning of the 17th, no penetrations were made, though a Navy plane circumnavigated the storm and reported winds (presumably flight-level) substantially in excess of 100kts at a radius of 30-40 miles from the center. Then in the early afternoon, another C-130 entered the storm while it was approximately 100 miles from the mouth of the Mississippi river. This is the flight that wound up feathering an engine and having to cut the mission short. Within the summary section of the preliminary report, it states that the “reconaissance reports indicated a central pressure of 901mb and maximum winds were estimated at 190mph near the center.” It’s not clear though whether this pressure was an actual measurement, or extrapolated in some way. The

Monthly Weather Review article is slightly different and a little more ambiguous stating, “The crew estimated highest surface winds to be 180kts. During the

penetration the aircraft was forced to feather an engine and had to leave the storm area, so that no further reconnaissance data was obtained until the storm crossed the coastline.” There is a footnote within the MWR article that states “Preliminary reports and other publications indicated a lowest pressure of 901mb. Recently a check of the raw data indicates this should be corrected to the 905mb value given here.”, so it seems plausible that in post-analysis the 901mb value was thrown out and, for continuity, they just went with the minimum value reported several hours earlier, on the evening of the 16th.

As for some of the suggestive comments we’ve seen in publications (MWR, Weatherwise, etc…) from engineers (including Herb Saffir and Robert Simpson themselves), I find it very, very hard to believe (though not entirely impossible) that they would intermix comments about surge damage with those about wind impacts. At the time, and even until much later, there was a pervasive belief that the relationship between wind strength and surge height was very finite… to the extent that, as everyone knows, it was initialy tied to the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale (SSHS). although it has since been removed. Obviously I want to assume that when they said winds had to have been “200 mph” to cause the damage observed, that they were talking exclusively about direct “wind” damage. That said, if they were, I’m still waiting to see examples (photographic or otherwise) of what drove them to that conclusion. On the other hand, and this is just random speculation on my part, if they inferred a wind velocity of 200 mph based on the extent of the extreme “surge” damage they were observing, then that’s seriously flawed by today’s standards and understanding of wind/surge relationships but, in 1969, I could see that as completely plausible. Similarly, if Camille’s maximum wind speed at landfall was “claculated” based on other data (such as the reported 909mb landfall pressure and/or the height of the surge), which I could also see happening, then that is also flawed, especially considering the lack of specifics surrounding the 909mb value and the aformentioned disparities we now know to exist with a wind/surge relationship. Two specific quotes from the immediately afer the storm point to this “blurring” between the characterization of surge-related damage vs. wind damage. Both are from Robert Simpson (et. al), from the 1969 Atlantic Seasonal Summary in the MWR (April, 1970):

“Maximum winds near the coastline could not be measured, but from an appraisal of the character of splintering of structures within a few hundred yards of the coast, velocities probably approached 175kt.”

The second quote is even more curious, and appears to imply that Simpson himself charcterized what is pretty obviously surge damage as “wind” damage:

“In the Pass Christian-Long Beach area, little trace of intact structures such as roofs or wall sections was observed within 100 yd of the coastline. Here, houses had been swept completely off their foundations and splintered into unrecognizable pieces, characteristic of the wind damage ordinarily associated with major tornadoes.” Even the two photos they provide as examples clearly show partial to total surge damage to structures, but all the trees in these shots are still heavily foliated.

So, in my opinion, since most of what has been readily available to the public about the storm came from well-respected engineers, and the director of the NHC himself, it has never really been questioned, has always been taken at face-value, and after a long enough period has just become part of the overall Camille legend that continues to perpetuate.

I strongly believe that when the re-analysis team completes their findings that they are going to lower Camille’s landfall intensity. That said, my suspcion is that, given the storm’s noteriety, and the continual speculation on a number of the points in question, they may wind up keeping it around 140kt (160mph), a low-end category five, which is still much better than the current 165kt (190mph).

Regardless of my particular findings, I’m sure many research scientists have looked at Camille (and other events) in excruciating detail, and it’s awesome that we can all share that information with each other and let everyone come up with their own conclusions. To that point, I’ve posted a set of Camille damage shots (compared to some other notable extreme TC wind events), and other relevant information in a Facebook gallery, which I’ll provide a link to here:

http://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.10150488164776778.364623.623936777&type=3&l=0fc38bed1c

Those who are interested are free to evaluate the information for themselves and make up their own minds.

You believe what you want to believe. I agree that there are things that don’t add up but in the end, I don’t believe there’s enough evidence to support one way or the other. The great thing about the Camille debate is that there’s evidence supporting both sides.

I trust that RH Simpson knew what he was talking about when it came to hurricanes. He was one of the most respected meteorologists of his day. But while I agree that those photos appear to depict storm surge damage and not wind damage, all data gathered for these reports were verified, especially pressures. This was even done in the early 1900s. I find it hard to believe that such a well-respected expert would make such egregious errors.

I just can’t get passed the Columbia reading. At first blush, you might think it was a collapsing core but in a collapsing core, the pressure tends to be unusually high with respect to the observed wind. The lowest pressure at Columbia was 958 mb, consistent with a 105 knot surface wind. It seems legit. Small storms like Camille tend to weaken very rapidly once inland and Camille would’ve moved into a higher friction, continental landmass very quickly (Columbia sits at 148 ft of elevation). This stands in contrast to Andrew, which passed over the wetlands of south Florida (10 ft ASL at best, Homestead is three). Even then, it still dropped 30 knots of intensity in six hours. Charley dropped three categories within just a few hours of landfall. The notion that Camille only dropped 25 knots of intensity after at least 3 hours and 18 mins over land (more than that if you count land interaction) just seems unrealistic to me.

That Camille was a Category 5 over the Gulf of Mexico seems well supported. Multiple SLPs lower than 910 mb were taken. 700 mb winds 20 n mi NW of the center were 140 knots while pressures were still falling and temperatures within the eye were still rising. That’s probably 120 kts at the surface (possibly higher as Camille was a small, convective hurricane that may have been more effective at bringing winds aloft to the surface). And this was nowhere near the strongest part of the storm. A 905 mb pressure supports winds in the neighborhood of 155 knots in your average hurricane (that’s a very rough, base estimate). In a smaller storm, that number goes up considerably.

Camille would’ve had to have dropped 25-35 knots in the 12 hours prior to landfall. I see no evidence of that in the available data. A more gradual weakening seems more likely. Based on all that I’ve seen, I believe winds at landfall were around 140-145 knots, and even that seems conservative. This number attempts to take a middle ground between the 125-130 knots suggested by the observed wind damage and the 150-155 knots suggested by the Columbia data, available recon data, and the Bay St. Louis bridge SLP (if accurate). But in my mind, there’s not enough data to say for sure.

As an aside, in nine years of studying historical hurricane events, I don’t think I’ve ever encountered more spectacular storm surge damage than observed in Camille. Camille utterly erased large, well-built, brick and masonry structures including multiple apartment complexes and large, antebellum mansions. The damage was indeed very reminiscent of extreme tornado damage. It’s been speculated that extreme winds may have contributed to these collapses.

These are just some of the points that I made during my discussion with extremeplanet above. Among others are questions about whether a weaker Camille would’ve had enough kinetic energy to produce a 24.6 ft storm surge (possibly 28 ft).

Mike Laca is a premier tropical weather expert and one of the most prolific hurricane chasers in history – as well as a good friend of mine. I just wanted to clarify who you were communicating with. The opinion shared by him is the same opinion shared by every well-known storm chaser I have ever broached the topic with.

(And the 28ft surge figure you mentioned appears to originate only as an un-cited anecdote on wikipedia, where false claims regarding Camille are added and removed with incredible frequency. Why Camille elicits such passion that some feel the desire to make-up incredible figures is beyond me.)

Well I’m a scientist. I trust scientists, not chasers. Like I said, I’m a semester away from a degree in meteorology and R.H. Simpson was one of the most respected tropical meteorologists and hurricane experts who ever lived. It is indeed true that there are many qualified experts (be they scientists or engineers) who question whether or not Camille was a Cat 5 at landfall and they have a legitimate argument. I was merely presenting my opinion.

And if you think, given the volume of destroyed structures, that 24.6 ft is the true maximum surge value, I believe you are mistaken. 28 ft is hardly an absurd or unreasonable number. Also note that I said “possibly” 28 ft. If I quote an unverified report, I present it as such.

I’m surprised you think that being an undergrad met major makes you a “scientist” and more qualified than the “chasers” who I mentioned. As a basic rule of respectful discourse, I’m also shocked you lacked the awareness to understand that “chasers” are often the “scientists” and degree-holders who conduct the damage surveys and provide the information that meteorology is built upon.

My point was that I’ve been studying these things for a long time and have been educated in the science of how these weather systems work. I’m not claiming to be an expert, I’m just saying I know what I’m talking about. I place greater trust in those who actually have degrees in their field of study.

Plenty of meteorologists with degrees chase storms. Most amateur or professional chasers, however, do not take part in official academic survey activities. Reed Timmer has a meteorology degree from the University of Oklahoma. That doesn’t mean I’m gonna take his word for it when he says, “that tornado was an EF5,” but it also means that he has the educational background to understand what he’s looking at, how it was caused, and the physics behind it, all very important when studying these events. An understanding of structural engineering is also important.

Michael Laca has been doing this a long time and has seen a lot of hurricane damage, but he’s not a meteorologist or an engineer. He’s a dedicated hurricane enthusiast with an opinion. I don’t believe you have the right to call yourself an “expert” in a field unless you have formal education in that field.

That doesn’t mean he’s not knowledgeable, he’s done a lot of great research, but he hasn’t been formally educated in meteorology and he’s trying to declare that some of the most respected hurricane meteorologists of the 1960’s and ’70s were wrong. Maybe they were, but until a degreed meteorologist conducts extensive, peer-reviewed research and explains scientifically why they were wrong, it’s all just speculation on our part.

I never claimed I was an expert! You’re unbelievable. I looked up Laca on his site. You can’t even begin to call yourself an expert until you’ve done the work that it takes to understand the science of this field. You wanna ban me, fine. Keep spouting your ignorant pseudoscience. I actually had plenty of respect for you and him before you made that statement. But fine, go ahead. You’re clearly incapable of having an honest, respectful discussion.

How do you know I’m not an “expert”? What was my undergraduate major – and what is my masters right now??

I went to the University of Miami, probably the university most synonymous with tropical meteorology, and I elected to graduate with a BOS minor in meteorology and switched my major since, ironically, I felt that the job opportunities available in met were rather limited and also I wanted a job that would allot me more time to chase storms.

I took every course related to tropical meteorology (even the one related research elective (ATM 308, I think?)) and I am now getting my masters in research methods/psychology. I volunteered at the NWS, have chased storms and spoken with more experts than most in my life, and now spend my school days specifically on the topic of research methodology.

So have you taken more classes on tropical meteorology than me? Is there a secret regarding meteorology you learned that allows you magical interpretive abilities to the same peer-reviewed articles and information we all can access? Of course, the answer is no. And despite the fact my educational history is greater than most online enthusiasts, I would never claim that put me in a league above the rest. Many of those I respect most do not have any weather-related degree – and they know much more than me.

And as for why you only “had” respect for Mike Laca when all he did was post a friendly, informative comment that wasn’t directed at you, I don’t understand. Anyways, see you later.

I’m not better than you. I don’t believe or wish to claim that I am better than you. I have a ton of respect for people that are willing to get their hands dirty and do the research: people like Michael Laca. I do believe that having an academic background in the subject gives one a better idea of how to interpret that data. But that doesn’t make us experts. I believe you need decades of experience in the field to be called that. I hold the term “expert” to a very high standard and I have a problem with certain amateur chasers (you know the chasers I’m talking about) who call themselves “experts” because they’ve chased a bunch of storms.

I was actually accepted to the University of Miami out of high school but chose to go to the University of South Alabama instead. It’s a small, tight-knit program with great professors and that’s what I wanted. I’ve taken the only tropical meteorology class they offer and have attended the annual fall tropical discussion seminars every year. I’m taking part in directed study research on the relationship between secondary eyewall formation and rapid intensification and have been researching tropical cyclones independently for nine years, including constructing my own TC databases. I’ve met many well respected members of the meteorological community, including Neil Frank and Chuck Doswell, at the annual SeCAPS conference held on campus. However, I have not yet met my idol Chris Landsea, whose reanalysis project I’ve dreamed of being a part of since high school.

It actually makes me sad that you and I have clashed because I think you’ve done some amazing work. I swear when I was looking for tornado damage pictures to go with some of the research on my website, your site wouldn’t stop coming up with these ridiculously awesome images. I used a few of them (properly cited of course). I don’t want to fight. I love meeting weather nerds. I love talking to fellow weather nerds. I don’t even necessarily disagree with you on Camille. I was just trying to make some counterpoints that I thought were worth mentioning.

I have no problem, and actually enjoy debating about meteorological events. My qualm primary qualm was the attitude I perceived – “I’m a scientist. I trust scientists, not chasers.” Maybe I picked up a tone you didn’t imply, but that sounded like a massive invalidation of the experienced storm-chasers and weather researchers I count as good friends. Anyone with extensive experience, as you say, deserves respect in their respective field, regardless of their college degree or lack of. Plus the whole point of my blog, to me, is the comments section – everyone can debate on an equal level using evidence as opposed to arguing over qualifications.

I also understand that there are thousands of online weather fanatics who take themselves far too seriously, and they do not know what it means to actually do the hard research work – you’re right, it does take dedication and knowledge and not just an encyclopedic knowledge of wikipedia facts.

Hopefully you do get involved in peer-reviewed research articles in the future. The science is ever-changing and malleable and always needs new perspective. I do sometimes wish I had continued with meteorology in school but I’m happy keeping it as a hobby for now and pursuing research methodology on a more general level in grad school.

I know you meant no harm, but be aware that the tone of written text can easily be misinterpreted.

Yeah I kinda put myself on a pedestal there and that was not my intention. Like I said, I hold the term “expert” to a very high standard. I don’t really like it being thrown around willy-nilly. And I’ve encountered a lot of chasers who think that running around with a video camera makes them an expert and it really bothers me. I think that colored my view of the situation somewhat and it shouldn’t have. The people I respect the most are the ones that are willing to do the work that it takes to really understand these events and don’t just skip to the fun stuff.